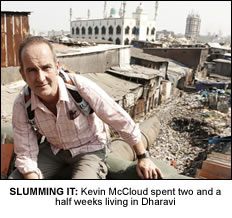

Kevin McCloud on life in an Indian slum as part of C4’s Indian Winter season

CHANNEL 4 kick-start their Indian Winter season this month which includes the TV premiere of Oscar-winner Slumdog Millionaire. As part of the season, Kevin McCloud – famous for fronting the Channel’s Grand Designs programme – presents ‘Slumming It’, a two-part series in which the presenter experiences first-hand life in slums of Dharavi – including life as a dustbin man. Here he discusses his experience with The Asian Today…

CHANNEL 4 kick-start their Indian Winter season this month which includes the TV premiere of Oscar-winner Slumdog Millionaire. As part of the season, Kevin McCloud – famous for fronting the Channel’s Grand Designs programme – presents ‘Slumming It’, a two-part series in which the presenter experiences first-hand life in slums of Dharavi – including life as a dustbin man. Here he discusses his experience with The Asian Today…

We’ve made two films in Dharavi, which is the slum in which Slumdog Millionaire was set. I was there for two and a half weeks living in the slum, some of that time staying with two families, learning about slums and re-cycling. I became a dustbin man for the day and did the rounds with the dustbin lorry emptying Mumbai’s rubbish and taking it to the dump and then meeting the recycling people. All the plastics, old car tyres, shoes and plastic bags and things were recycled then chopped up, washed and graded, all in the slum – a place with a £500 million turnover every year. It’s incredibly industrious, everybody’s got a job, nobody’s begging – you can’t use the word ‘slum’.

Do the people there see Dharavi as a slum?

Actually it’s really interesting, I said to people ‘what did you think of the film?’, and they went, ‘well, we really like the film, but we don’t like the title because this is not a slum [although technically it is] and we are not dogs’. People are really, really proud of living there, although a lot of them don’t tell the outside world they live there. A lot of people who live there work in the city in offices, and go to work in the most beautifully dressed clothes. They have immaculate wardrobes – all the men’s shirts were pressed. For the two and half weeks I was there, I was the scruffiest individual in the whole place. I kept feeling really embarrassed and self-conscious about my linen shirt that was un-ironed, my chino trousers and my walking boots. They were all wearing sandals, and the women were all dressed in the most gorgeous clothes, the kids go to school in the most beautifully pressed school uniforms, and their hair all done. This is a place where people are amazingly happy and remarkably industrious. So you can’t really use the word ‘slum’… until you look down and realise you’re side stepping the ‘land mines’ [faeces] and there are rats and a lot of vermin cockroaches, and the sewage is primitive, and the mains water comes on for three hours a day and it’s shared between several houses out of one tap. There are about five people to a room, the size of a small single bedroom; living, eating, sleeping, cooking, working in that space, you realise things are not as rosy.

Dharavi has been cited by some people as being something of an exemplar, a place we could learn a lot from, hasn’t it?

Prince Charles has been there, and Prince Charles cited it together with lots of other New Urbanists, as an example of durable, sustainable, flexible new living. There are lots of lessons there; lots of technical lessons about public space and how we use space, and how many people it takes to build a community and how communities work, and what makes people happy. All those questions can sort of be addressed in Dharavi.

Can it really be seen as an ideal place to live?

Well, no, that’s not the whole story. India as a whole has got 80% illiteracy. People who live in this place are not aware of the health implications of their surroundings, they’re not ware of the toxins in the air from burning the stuff in the fire, they’re not aware of the diseases that rats carry. In the slum you’ve got cholera, TB, denghi fever, bubonic plague. So if you’re bitten by a rat it’s serious, you’ve got 48 hours when carrying the bubonic plague before you’re dead. And if you’re able to get any treatment, you only have a 50/50 chance. Anybody that describes these places as exemplary looks at them with quite a blinkered view. There’s lots of good stuff there, but are we really suggesting that in the UK we should live five people to a room? Are we really suggesting that these people stay as they are and they carry on living in these conditions? Of course not. So I’m really sceptical about seeing these places as exemplars.

As India becomes richer and the economy begins to grow, will places like Dharavi disappear?

What’s going to happen is that India’s environmental foot print is going to go through the roof – there are one million people living there. And this is the real dilemma; who are we to deny them an improvement in their standard of living? At what point do we stop? Do we let them achieve a standard of living like our standard of living or do we have any right to prevent them from doing that? Because if we do let them, then all the efforts from our government to reduce carbon emissions would be useless. It only takes India to double its carbon footprint by 2050, from two to four tonnes per capita, for it to wipe out everything we do in Britain five-fold. There are one million people living there, and they all get to improve their standard of living, but that means a much bigger drain on the entire planet and its resources. So I came away with more questions than answers.

Were you prepared for the level of poverty that you encountered out there?

I’m uncomfortable with the word ‘poverty’, it’s such a negative term, and I can’t use the word ‘slum’. ‘Slum’ is a technical term that describes a place without a certain level of sanitation, healthcare and education and Dharavi conforms to that, so in that sense, its Asia’s biggest slum. As for the word ‘poverty’ it’s such a charged word. There are people there living on almost nothing, in tiny rooms the size of the average British bathroom, with five people in that tiny space with no natural daylight, no ventilation, vermin all around, crap outside – by which I mean excrement – dog excrement, rat piss and shit, dead animals, a sea of plastic bags outside their back door in dark grey, gooey liquid which is basically chemical effluent. I mean it’s almost the worst physical environment you can imagine a human being having to live in. These people emerge from these little holes, dressed in the most beautiful clothes, immaculately pressed, hair all shiny and perfect, and they’re happy, very happy indeed. I’ve filmed and been to places in Britain on council estates where I have climbed staircases with the crunch of needles underfoot, and found people very heavily drug dependent, living in squalor. And actually I think, who’s the poorer for that; is it the people living with nothing? I’ve seen worse poverty here and seen worse physical degradation. The physical conditions there are really bad, the human scope appears totally contrary to that. The only thing I hold on to is that India is a place of extreme paradox and opposites. And for every moment of joy, there’s a moment of terror, and for every beautiful encounter, there’s an awful one too – in a way they go hand in hand.

With that in mind, the joy and terror and good and bad encounters – were there moments when you felt threatened in Dharavi?

With that in mind, the joy and terror and good and bad encounters – were there moments when you felt threatened in Dharavi?

There were two moments when I felt threatened in Dharavi – well one was in Dharavi, actually and the other was in Mumbai. In south Mumbai, beggars knock on the car windows and stop you in the street because they want money. There’s a sense of naked aggressive competitiveness really. It’s a city and it’s a financial city, like New York, no one stops, everything’s moving fast and furiously. In the slum, not one person asked me for money, but I did go to this industrial area, looking for this bloke called Mobin who does a lot for the factories which are in the slum. I walked into what was an Islamic area, and I hadn’t been there before and didn’t know what the result would be and whether they would be different from the Gujaratis, and people just blanked me every time I mentioned this guy’s name. People just looked at me quite passive aggressively. You get that in the slums, you get people just looking at you and almost blanking you. It’s curiosity, it’s a strange curiosity they have, it’s nothing more than that. They’re just absolutely bewildered as to why you, a white person, should be there – what are you doing there? Dharavi has this reputation of being this den of vice and iniquity, a place of absolute squalor, where you will get your throat cut. But the people are delightful, and I felt absolutely at home there. I’ve been reading about the slums in London in the 1880s, and they were portrayed at the time as places of squalor and disease, full of immorality and violence, but actually 95 per cent of the people there were common, decent people trying to make a living. It’s just the same in Dharavi.

You’ve touched upon the recycling project there. It’s a massive part of life in Dharavi, isn’t it?

Yes, 35,000 people work in Dharavi on recycling. Eighty per cent of Mumbai’s rubbish is recycled in Dharavi. That’s a city of 16 million people. Everything is recycled, from plastic bags to tiny things like the tiny plastic tubes that go inside perfume bottles. All of the people who work on it are self-employed, and one sells to the next who sells to the next who sells to the next. And at each stage in the recycling stream, somebody separates the waste a bit more. It all happens in tiny little workshops or shanty shacks. I went to one that was really filthy, rat-infested, flies everywhere and really grim, no natural light. There were three people squatting down sorting out three types of thing. One was aluminium, which can be melted, and they melt it right there and poison themselves in the process. One was plastic spoons. And one was plastic straws. There was a bloke my age just sitting there sorting out plastic straws. That’s pretty grim. But they just get on with it.

You also met with elements of Mumbai’s high society while you were there. Was that quite a jarring contrast?

The thing about Mumbai high society and fashionistas is that it’s no different from going to a party in London, really. There are always going to be people who want to act like they belong in the pages of Hello! I’m not saying it was distasteful, but it was quite weird to find a Mercedes-driving banker and his glamorous wife, who’s had three facelifts, in comparison with someone living in Dharavi. But the people cooking the food for that event, and the bloke on the door, came from the slums, so you must never assume that the people in Dharavi don’t understand that other life. They know all about it. They’re enmeshed into Mumbai culture, and Mumbai couldn’t survive without them.

What lessons have you brought home from the trip?

Always to carry bacteriacide hand gel out there. Fundamental! And always to drink bottled water. It was a great irony that there we were, filming all this recycling, and what were we doing? Guzzling back imported water, from the foothills of the Himalayas – where there’s plenty of water, because the Himalayas are now melting, so bottled water is in abundance. What did we learn? A great deal about society – how many people you can fit together in one space and it still be tolerable. We learned about what makes people happy, to an extent. Or rather, what doesn’t make people happy – in terms of the fact that materialism and standard of living seems to have surprisingly little effect on the happiness of people there. I learned about the distinction between the squalor of your environment and the very Indian way in which people take special care of themselves. I’ve always talked about how important the built environment is, how architecture can change our lives, and make us happy, or happier. And I’m beginning to think that you can find happiness in other ways, and that people are fundamentally what makes life tolerable and pleasant, interesting and beautiful.

Kevin McCloud: Slumming It, part of Channel 4’s Indian Winter season, on Thursday 14th/15th January on Channel 4.