How the Channel 4 thriller ‘Britz’ came about

On July 7th 2005 four men strapped explosives to their bodies, walked into the heart of London’s transport network and blew themselves up. Fifty-two people were killed, in addition to the bombers; three weeks later, four more men tried to do the same.

On July 7th 2005 four men strapped explosives to their bodies, walked into the heart of London’s transport network and blew themselves up. Fifty-two people were killed, in addition to the bombers; three weeks later, four more men tried to do the same.

None of them were mercenaries or émigrés sent from abroad. No one spotted them, they didn’t stand out. They were born, brought up and educated here – Manchester Utd supporting, iPod owning, dress-like-us, speak-like-us people. They were Brits.

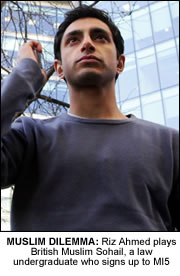

Britz is a story in two acts. Sohail and Nasima are a young brother and sister born and bred in Bradford, whose constantly overlapping lives end up taking perilously different paths. The first film tells Sohail’s story and the second Nasima’s. From two differing points of view, we watch their hopes and ideals clash with the reality of being a young Muslim in Britain today.

Britz is a fiction, a thriller, but it is set squarely in the real world. It deals with the notion of identity and divided loyalties, the duality of being both British and Muslim. The title of the drama comes from the Muslim predilection for shortening first names and ending them with a zed – Nasima’s friends call her Naz. Britz takes the raft of immigration, anti-terror and anti-social behaviour legislation that has been introduced since 2001 and asks what it actually means for citizens on the ground, in particular those who are British and Muslim.

But the idea for the films, according to Peter Kosminsky, started with the July 7th bombings. “It was pretty clear what the next film [after The Government Inspector] should be,” he says. “We had to try to figure out how that could come about.” Britz therefore explores how a young intelligent British Muslim could feel so disenfranchised, so powerless and become so angry at their country of birth that they would commit an extreme and despicable act and ultimately it asks how we can ever hope to prevent such an incident re-occurring?

Kosminsky considered telling the personal stories of the July 7th bombers, in the way he had told the story of David Kelly in The Government Inspector. But in light of his own experience as a second-generation immigrant, he wanted to look more generally in to second-generation Muslim disillusionment with Britain (domestic and foreign policy in particular.) “I decided, in discussion with my colleagues, that the best thing was to fictionalise it – to research the way Muslims think and feel at the moment – and then try to create some fictional characters drawing on what we’d learnt.”

That research was spread over two years, and used a team of researchers, including Ali Naushahi, a second-generation Asian Muslim brought up in Bradford and now working in the television industry. A wide range of interviews with young Muslims were carried out over several months. Kosminsky also consulted at length with organisations like Liberty and Amnesty on the alienating effects that recent legislation and foreign policy were having on the Muslim community. “It became very apparent from the research our team was carrying out that these were matters about which British Muslims felt very, very deeply.”

Alongside a special Muslim on-set advisor, a significant proportion of the cast were Muslim. Throughout auditions and rehearsals they added nuances and adjustments to dialogue, dress and ritual. “It was a constant process of learning,” says Kosminsky. He cites one example that came out of his research into a funeral and burial scene. “I went to the Central Mosque in Leeds, effectively on a location recce. We came into this room, which resembled an operating theatre, and they explained that in this room the body is ritually washed three times by the same sex relatives and friends of the deceased. They described it to me in great detail, and I thought what an incredibly moving and poignant moment it must be for all those involved. So I went back to the hotel and I wrote such a scene into the script. They very kindly agreed to let us film it in situ.”

Alongside a special Muslim on-set advisor, a significant proportion of the cast were Muslim. Throughout auditions and rehearsals they added nuances and adjustments to dialogue, dress and ritual. “It was a constant process of learning,” says Kosminsky. He cites one example that came out of his research into a funeral and burial scene. “I went to the Central Mosque in Leeds, effectively on a location recce. We came into this room, which resembled an operating theatre, and they explained that in this room the body is ritually washed three times by the same sex relatives and friends of the deceased. They described it to me in great detail, and I thought what an incredibly moving and poignant moment it must be for all those involved. So I went back to the hotel and I wrote such a scene into the script. They very kindly agreed to let us film it in situ.”

Muslim extras for the scene were recruited from the Bradford area. “It turned out that each of them had washed the body of a friend or family member in their lives, one for a close relative just a few weeks before in the very room in which we were to be permitted to film. So we were shooting in the real room, with the words written out by the Imam, with people who had been involved in similar experiences recently in their own lives. It was gut-wrenching – the emotion was incredible because it felt so real.” A chance remark on a recce had led to what Kosminsky thinks is one of the most powerful sequences in the film, based on a ritual that has rarely if ever been previously filmed. The authenticity of the drama was very important and Peter puts that down to the input of the many Muslims working on the film. “They were very generous with their knowledge and experience and helped us to get it right. We all got caught up in the emotion; it felt like we were in the middle of a documentary.”

Drawing together the various strands from his research, Kosminsky reached his conclusion: “There’s no doubt – although I don’t think that Tony Blair ever actually admitted it – that the level of alienation caused by Britain’s recent foreign policy is enormous.” British Muslims, he found, feel a strong sense of ‘Ummah’, the collective Islamic consciousness that connects them to other Muslims across the world. “It’s not something they pay lip-service to – it’s in the Koran and it’s central to their faith.” When set against Britishness, he found that young British Muslims were caught between conflicting loyalties – particularly at a time when many of them feel that much of the new anti-terror legislation is aimed at them. It’s this dilemma that he has brought to life in Britz.

It’s also a dilemma that he says he feels himself. As a second-generation British immigrant, Kosminsky sees Sohail and Nasima as personifying his own internal dialectic. “I’ve felt throughout my life a sort of tug and pull of different allegiances – whether to try to dig in to British society and be as British as I can be or whether to overturn the applecart. That was always going to be a factor and in fact, wanting to write a bit about my own confused sense of my identity was part of why I wanted to do it.”

Like all of his films, however, there is also a strong political undercurrent that gives Britz its bite. “I started as a journalist and I made documentaries for many years and I see myself first and foremost as there to ease the curtain back a little and peek behind it. If a film seemed likely to be a gentle meander which wouldn’t upset anybody or make people question something about the nature of our society in some way, I probably would walk away from it.”

The result is a film that harnesses the visceral power of the best thrillers to ask some awkward, complex, and yet hugely germane questions about contemporary Britain. As Liza Marshall, Channel 4’s Head of Drama, says, “We first and foremost want to make great drama – if the drama can reflect contemporary society that’s all for the better. Britz does both. It is exactly the sort of drama that Channel 4 should be doing – a provocative, challenging film that no other channel would make.”

Britz is on Channel 4 on 31st October and 1st November

Related Links: